By Clarissa Stevens, Fran Proctor, Amanda Boorman, Barbara Rishworth, Abbie Unwin, Brid Featherstone, Andy Bilson

Introduction

This article presents summaries of contributions made at the Rethinking Fostering and Adoption: Achieving social justice in practice plenary during the Social Work Action Network (SWAN) conference on 6th April 2019 at Liverpool Hope University. The session brought together speakers with a range of lived experience including as an adoptee and Childhood Trauma Specialist (Fran), a birth parent with experience of involvement in child protection proceedings/co-founder of the ReFrame Collective (Clarissa), adoptive parent, campaigner for open adoption reforms and founder of the Open Nest charity (Amanda), and social work academic and co-author of the British Association of Social Work’s (BASW) Adoption Enquiry (Brid). For this article, further additional contributions come from Emeritus Professor of Social Work (Andy) and co-founders of the ReFrame Collective (Barbara and Abbie).

The article combines brief summaries which give a sense of the diversity of the conference contributions, whilst reflecting a shared view that the current child protection and adoption system requires radical transformation in order to become more humane, supportive and socially just. The first two sections of the article outline the ‘investigative turn’ in children’s services, and key findings from the BASW Adoption Enquiry respectively. The third, fourth and fifth sections make the case for radical reforms of the child protection and adoption systems from the perspectives of those who are most directly affected, adoptees and birth families, offering a range of views on the need for support, inclusion and the importance of preventing trauma.

All of the contributors are active campaigners for reform of the child protection and adoption systems, and their social media and contact details are given to enable readers to find out more and get involved with these initiatives.

The ‘investigative turn’ in children’s social care services – Professor Andy Bilson

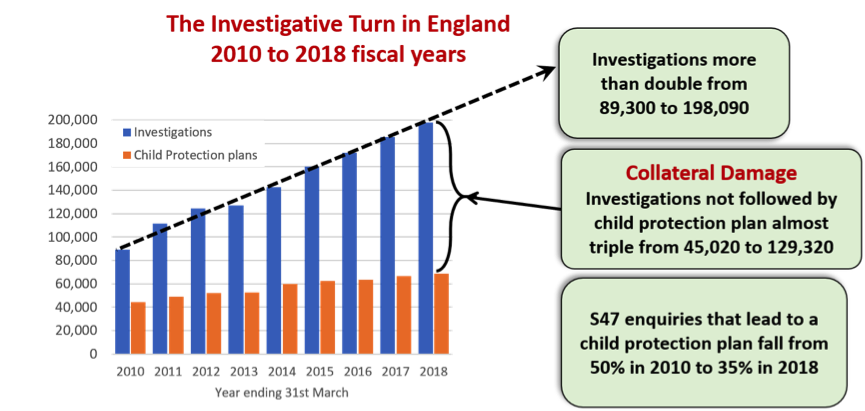

In England and other English speaking countries there has been an “investigative turn” with a huge change in the way that children’s social care responds to concerns for the welfare of children. There have been cuts in support for families and increases in child protection investigations leading to more children separated from parents. The number of section 47 investigations has increased every year since 2005. The graph below shows this trend between 2010 and 2018. Investigations doubled because the proportion of referrals leading to an investigation increased from 15% to 30%. One in every 16 children were investigated before their fifth birthday in 2017.

As investigations increased they became much less likely to be followed by a child protection plan. In 2010, 50% of investigations led to a child protection plan, this fell to 35% in 2018. The 129,320 investigations not followed by a plan in 2018 cause collateral damage harming families and children who are unlikely to receive or accept help even where they have difficulties.

Where plans are made there has been little or no change in the numbers of those for physical or sexual abuse since 2010. All the increases have been in neglect or emotional abuse. I found that the increases in emotional abuse plans varied depending on the local authorities with some having very large and sudden increases whilst in others rates fell. These patterns are unlikely to stem from differences in levels of abuse in the community.

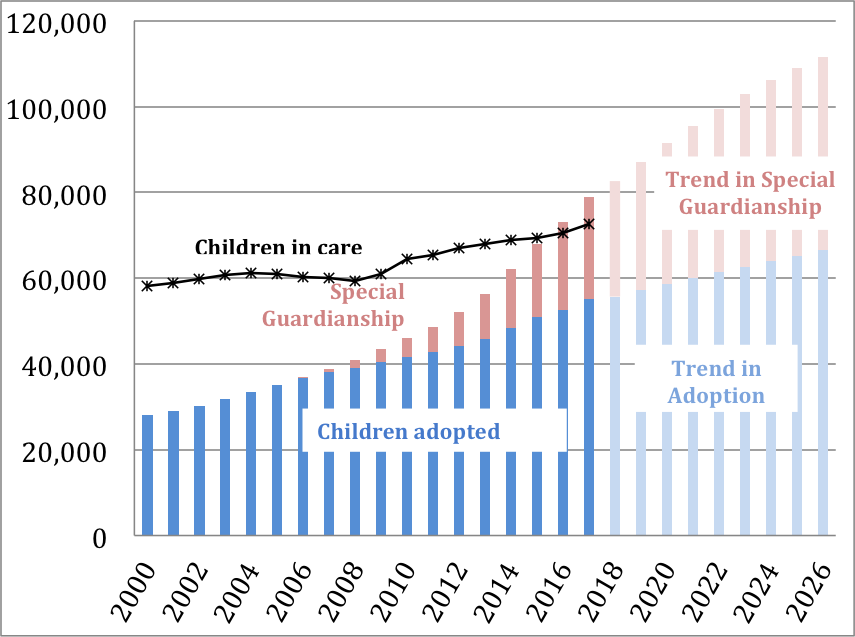

The numbers separated from parents have risen due to the increase in the number of children who on any one day are adopted from care, and increases in long stays in care. The graph shows how, despite the fall in new adoption placements since 2014, the number of children under 18 in adoption or special guardianship placements on a census date is now higher than the number in care despite this also having risen since 2008.

The graph also shows how the number of children in adoption and special guardianship placements will continue to increase reaching 111,500, almost 1% of those aged 0 to 17 in 2026 if the 2017 rate of placements continues until then.

Many children taken into care and those adopted have parents who have been in the care system. In 2014-15 at least 32% of all adopted children in Wales had one or both parents who were in care at age 16. Many more children had parents who had been in care but left before being 16. Similarly, 40% of parents who had recurrent care proceedings had been in care themselves.

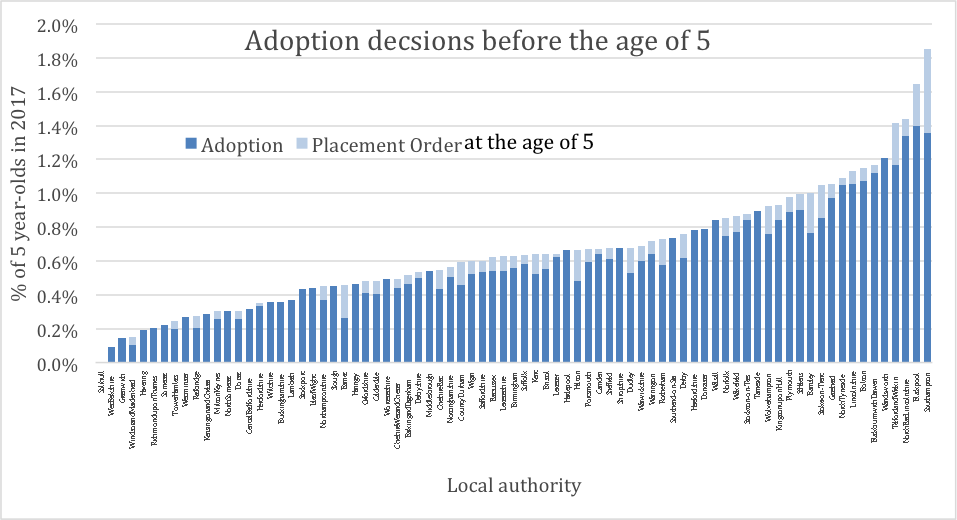

I found that across England where rates of adoption from care had increased the numbers of children in care are also increasing whilst in local authorities with lower rates the numbers are decreasing pointing to a ‘culture of rescue’ in some areas. Also where adoption rates before the age of 5 had risen most child protection activity had increased by 96% compared with an average increase of 21%.

There were large differences in rates of children adopted not explainable by levels of deprivation. The graph below shows that 1.9% of all children in Southampton were adopted before age 5, far higher than any of its statistical neighbours. Differences are due both to rates of deprivation and a culture of rescue in some agencies.

This data thus shows the rapidly increasing use of investigations in response to families in difficulty alongside the increases in children removed from parental care. The large differences between local authorities suggests that these trends are affected by the decreasing support for families, increasing deprivation and a growing local culture of rescue.

Further information: bilson.org.uk or @Andy_Bilson

The role of the social worker in adoption: ethics and human rights – Professor Brid Featherstone

While historically adoption has been promoted across the political spectrum and has often been attended by controversy, renewed concerns about particular aspects of this policy became evident from 2010 onwards especially in England. The push by policymakers to increase adoption numbers in the context of austerity, the use of reduced court timescales, and the number of adoptions that dispense with parental consent became the focus of attention from a range of national and international commentators.

Such concerns became framed by the British Association of Social Workers (BASW) as ethical and human rights issues and led it, in 2016, to commission: ‘The role of the social worker in adoption – ethics and human rights: An enquiry’

In total 300 individuals and 13 organisations contributed to the Enquiry. Social workers or managers with a social work background were the largest group (105), followed by birth family members (56), adoptive parents (44), adopted people (32), academics (24) and related professionals (24).

The key findings were:

- The use of adoption needs to be discussed in the context of wider social policies and the impact on already disadvantaged families and communities.

- The current model of adoption fails to recognise multiple attachments and complex identities.

- A rethink of contact arrangements between adopted children and their families is needed.

- There is little evidence of human rights talk among social workers.

- Social workers were, however, concerned about the reduction in resources for birth families and the policy emphasis on adoption in that context.

The Enquiry report is available at www.basw.co.uk/resources/role-social-worker-adoption-ethics-and-human-rights-enquiry

Further information: @Acsocialwork

The need for radical transformation of the child protection system – Clarissa Stevens, Barbara Rishworth and Abbie Unwin (ReFrame Collective)

ReFrame is a collective of parents with experience of the child protection (CP) system, professionals and academics. We are passionate about seeing change in how we support parents and families who are at risk of becoming, or are involved in care proceedings in relation to their own children. We believe that the current CP system requires radical transformation in order to become more humane, supportive and socially just, and that parents should be centrally involved in this transformation. We recognise the need for systemic change that acknowledges the political ideologies that underpin our current social care and health systems. We aim to create opportunities to promote the social inclusion of birth parents, while raising awareness of their experiences, through direct support, co-produced projects and social action initiatives.

Austerity policies alongside a risk-averse context have led to the numbers of parents involved in the CP system rising, with the number of babies removed from parents doubling in the last 8 years. Local authorities are under immense pressure to do more with less and to ‘keep children safe’ without frameworks that address the fundamental underlying factors e.g. poverty, deprivation and disability. Certain groups are disproportionately involved in the system, e.g. those who have grown up in care are 66 times more likely to have their children taken into care (Jackson & Simon, 2005), those exposed to domestic violence (48.1%), and those who have experienced four or more adverse childhood experiences (56%), yet contextual issues are overlooked with social inequalities/socio-political contexts being translated into individual problems and diagnoses (Broadhurst et al., 2017).

Dominant narratives held about parents have resulted in their being positioned in limiting ways. Parents have described feeling marginalised by the current system, talking of the scrutiny they faced rather than of receiving support. For example, there are cases in which women in relationships characterised by domestic violence are criminalised for failing to protect their children from abusive partners, obscuring the complexities of such situations. Women have described being unaware of the violent and abusive nature of their relationships, fearing leaving or feeling that there is nowhere else for them to go, and feeling caught in a ‘catch 22’ situation in which they hide their relationship from professionals for fear of the repercussions. The positioning of parents within the current system often leaves them without adequate or appropriate support (Broadhurst et al., 2017).

As a collective, ReFrame draws on Liberation Psychology approaches and Community Psychology. These approaches recognise the role of power and privilege in the health and wellbeing of a community, and believe that people affected by a problem have unique knowledge and skills to inform solutions. We feel it is essential that the voices of parents, adoptees and those in care are placed at the centre as a justice issue, in order that we can begin to understand the lived experiences of people who have been involved in the CP system. Only then can we begin to develop and transform services accordingly.

We aim to reframe dominant narratives about parents by raising awareness of the contexts and inequalities involved in the current CP system. We currently provide co-produced training and consultation and are keen to collaborate with parents and professionals on collective awareness raising projects. We hope to create a UK-wide network of organisations and individuals advocating for wider systemic change.

If you would like to get in touch you can follow ReFrame on twitter @re_frame_ or email us at admin@reframecollective.co.uk.

Campaigning for radical reform of the adoption system – Amanda Boorman (founder of Open Nest)

The Open Nest charity has been campaigning for radical adoption reform since it formed in 2013. Its trustees came together as a group of people all affected by adoption from different perspectives (mostly either adoptees or adopters) but all dismayed at the conservative governments ‘adoption drive’.

This drive towards adoption reform began with Michael Gove who shifted £150 million from the Early Intervention fund to adoption recruitment and reform. This failed to put adopted people themselves at the forefront of development, and removed support services such as family centres that helped parents.

Alongside the harsh politics of austerity the very worst aspects of adoption were held up as positive including quicker removals of children, shortened timescales for adoption placement, and contact with birth families made less important and more difficult. Alongside this, the Adoption Support Fund turned the loss and grief experienced by both children and adults in the adoptive process into a condition for which government funded and private agencies could create marketable products.

Adoption in the UK is currently set against a cultural and social background where a women who has experienced being in care is 66 times more likely to have a child removed than a woman who is not care experienced. Where living in certain parts of the country means you are far more likely to have a child removed than a family living elsewhere. Where a large proportion of learning disabled women have children removed and where women who are victims of domestic violence and abuse can lose their children forever.

Adoption currently fails to recognise that it cruelly ignores poverty, inequality and injustice against women. Adoption recruitment takes place outside affluent supermarkets and children are marketed on Twitter.

Open Nest have refused to accept or apply for government funding for the work we do supporting those upon whom adoption has had negative and life changing consequences as it would potentially silence our opinions.

We believe that this reform period will be looked back upon with shame and a time when many social workers felt they were carrying out work in line with policies they felt uncomfortable with.

Now is the time for adoption professionals to speak out and stand up for family rights and in particular women’s rights in relation to adoption policy and practice.

Further information: www.theopennest.co.uk/ and @TheOpenNest or @BoormanAmanda

Supporting Adoptees and Preventing Trauma – Fran Proctor (Adoptee and Childhood Trauma Specialist)

I believe in many situations open adoption can be an appropriate intervention on behalf of children who need to keep important links to their birth families and family history. However, and although being a minority, there are children whose parents were abusive, violent and in some cases have committed serious crimes.

My personal story of adoption and the care system is that my sister and I were removed due to abuse. I was adopted and my sister was returned. My sister was murdered at the age of 7. How this information was later delivered, assessed and recorded created huge amounts of unnecessary secondary trauma for me which impacted my life greatly.

Five things that I believe would have potentially prevented additional trauma in my own life, and would reduce added trauma in the life of a child or young person who has been removed due to abusive or an abusive biological parent, are:

- Not encouraging the adoptee to identify with birth family culture unless this comes from the individual themselves. Assuming that we would want the same identity as an abuser or someone who has abused us can be really traumatising and may leave us feeling like we will turn out the same or that we are inherently flawed.

- Searching for answers and asking questions about our past does not mean we are asking for a relationship, and this assumption should never be made. Therapeutic support should always be available though to make any informed choices about the future and any contact if asked for.

- Find healthy ways to help a child or a young person to make small steps forward the best they can. Talking over and over about the past and any trauma can put an individual in a place of re-traumatisation only to impact negatively on mental health and wellbeing causing more problems in everyday life.

- Being adopted/removed means that you live a parallel life to a greater or lesser extent. New information that comes to light should be delivered in a timely, age appropriate, safe and careful manner so that there are no huge shocks that are so overwhelming that it makes it impossible to cope.

- It can be assumed that once you are adopted/removed, and once you have a different life everything is okay, you are okay. This is usually not the case, and what a lot of children and young people need to hear is that it’s okay to not be okay, and that the things that have happened are not their fault.

Further information: @Fran_Proctor, www.franproctor.co.uk or havening.org/directory/grid/view/details/14/653-Fran-Proctor